Can Continued Exposure to Anesthesia Cause Problems With the Brain Adults

Introduction

In humans, surgery under general anesthesia has been linked to performance deficits in memory and executive function (Monk et al., 2008; Rundshagen, 2014). The specific aspects of surgery that lead to cognitive dysfunction are unknown, but prolonged exposure to general anesthesia has been implicated as a possible contributing factor. These findings raise significant concerns for animal studies in biomedical research as many utilize anesthetics for surgical procedures that may lead to unintended cognitive impairments and/or neurological changes that may confound results if not appropriately accounted for. Preliminary studies show that certain sedative agents can improve (Gertler et al., 2001; Hovaguimian et al., 2018) or worsen (Pandharipande et al., 2006) postoperative outcomes, suggesting that postoperative cognitive dysfunction may be linked to the pharmacodynamics of specific anesthetics rather than surgery or the sedation process itself.

Thus far, most rodent studies have focused on neonates and aged animals, as these two age groups appear to be particularly vulnerable to cognitive impairment following anesthesia exposure. Several reports have found that cognitive impairments can arise in rodents following the administration of anesthesia independent of surgery (Culley et al., 2007; Callaway et al., 2016). More specifically, anesthesia exposure in early life impairs performance on spatial memory and fear conditioning tasks even into adulthood (Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 2003; Stratmann et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010; Kodama et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2013; Landin et al., 2019). In aged rodents, sedation with volatile anesthetics such as isoflurane negatively affects performance on spatial memory, fear conditioning, and odor-reward association tasks (Culley et al., 2003, 2004a,b; Ku et al., 2010; Erasso et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012).

The neural mechanisms connecting sedation and cognitive dysfunction remain elusive, but one possible link is a reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis. Similar to the behavioral effects of anesthesia, decreased postnatal generation of granule neurons in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus is also associated with impaired learning and memory (Cameron and Glover, 2017) as well as depression (Hill et al., 2015). A significant proportion of granule cell population is generated in the juvenile period (Bayer et al., 1993; Kozareva et al., 2019), so any dysregulation during this period could have large and long-lasting effects on the dentate gyrus. Conversely, in old age, the rate of DG neurogenesis is quite low (Kozareva et al., 2019; Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2019) such that further decrease could leave the DG without sufficient new neurons, making this age group vulnerable as well. The generation of functioning neurons in the DG requires several weeks and involves division of precursor cells, development of a neuronal phenotype, survival of only a fraction of the young neurons, and integration of the new neurons into circuits, and each of these phases can be independently altered by drugs and experiences (Snyder et al., 2009a,b; Soumier et al., 2016). In rodent studies, there is significant evidence that both inhalable sedatives (e.g., isoflurane and sevoflurane) and injectable sedatives (e.g., propofol) can increase cell death and reduce cell proliferation in the neonatal DG (Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 2003; Stratmann et al., 2009; Broad et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Palanisamy et al., 2017). No changes in cell proliferation or cell death in the DG have been observed following treatment with isoflurane or propofol in aged rats (Ku et al., 2010; Erasso et al., 2011, 2013), but isoflurane decreased survival of 21-day old cells in these animals (Erasso et al., 2013), indicating that the effects of anesthesia on neurogenesis and cognition vary considerably across the lifespan.

Far less attention has been directed toward examining anesthesia-induced cognitive dysfunction in young adults, and the effects that have been observed are often unclear or seemingly inconsistent. Administration of propofol, but not isoflurane, impaired performance of an odor-reward association task in adult rats 2 days after anesthesia (Erasso et al., 2011). Similarly, sevoflurane and isoflurane seem to have opposite effects on behavior in a spatial water maze (Stratmann et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2013). Studies in young adult rodents have found negative effects of sedation on adult neurogenesis (Erasso et al., 2011, 2013; Krzisch et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2014), but many experiments have not found changes in new neurons after sedation, suggesting selective effects of different sedatives (Erasso et al., 2013), at different time points after anesthesia (Erasso et al., 2011; Krzisch et al., 2013), and different phases of neurogenesis (Erasso et al., 2013). Additional studies are required to determine the impact of sedatives on neurogenesis in young adults.

In the current study, we investigated the effects of four different sedatives on generation, maturation, and survival of new neurons in the adult rat DG using endogenous markers of proliferation and neuronal maturation state as well as injectable birth dating markers. Most studies examining the effects of sedation on adult hippocampal neurogenesis have focused on isoflurane and propofol as they are commonly used in clinical and research settings for both deep anesthesia and procedural sedation. While the exact mechanism of action is unknown for these drugs, their sedative effects appear to require activation of GABAA receptors (Garcia et al., 2010). Dexmedetomidine is a potent α2-adrenoceptor agonist commonly used for sedation in laboratory animals as well as human patients that reportedly causes less neurocognitive dysfunction and respiratory distress than many sedatives (Gertler et al., 2001). Midazolam, the only water-soluble benzodiazepine, is commonly used for procedural sedation in humans and is increasingly used in animal studies (Olkkola and Ahonen, 2008). We therefore sought to compare the unknown effects on adult neurogenesis of these less investigated two sedatives with those of isoflurane and propofol.

A handful of studies in neonatal rats have observed sex differences in the cognitive effects of sedation (Cabrera et al., 2020). However, the vast majority of investigations into the effects of sedation on cognition and neurogenesis in adults have been done in male rodents, mirroring the predominant use of male subjects in neuroscience and animal research more broadly (Beery and Zucker, 2011). Research examining sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics has recently gained more attention due to concerns regarding the overdosing of females on several drugs (Soldin and Mattison, 2009; Cahill and Aswad, 2015), underscoring the potential problems of preclinical research limited to one sex. Therefore, the current study included both males and females to assess potential sex differences in anesthesia effects at different stages of adult neurogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

A total of 42 male and 42 female adult Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC, United States) were used (n = 6–8/treatment/sex). Isoflurane and Propofol were tested in one set of animals, and midazolam and dexmedetomidine were tested in a second set, each with a separate control group. Upon arrival at postnatal day (P) 49, rats were group housed in a reverse 12:12 light/dark cycle (Lights off 9:00 AM) and acclimated to the animal facility and investigator handling for 1 week (Figure 1A). On P56, all rats received a single injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma; 200 mg/kg; i.p.). Three weeks later (P77), all rats also received a single injection of ethynyl-deoxyuridine (EdU, Cayman Chemicals or VWR; 50 mg/kg; i.p.).

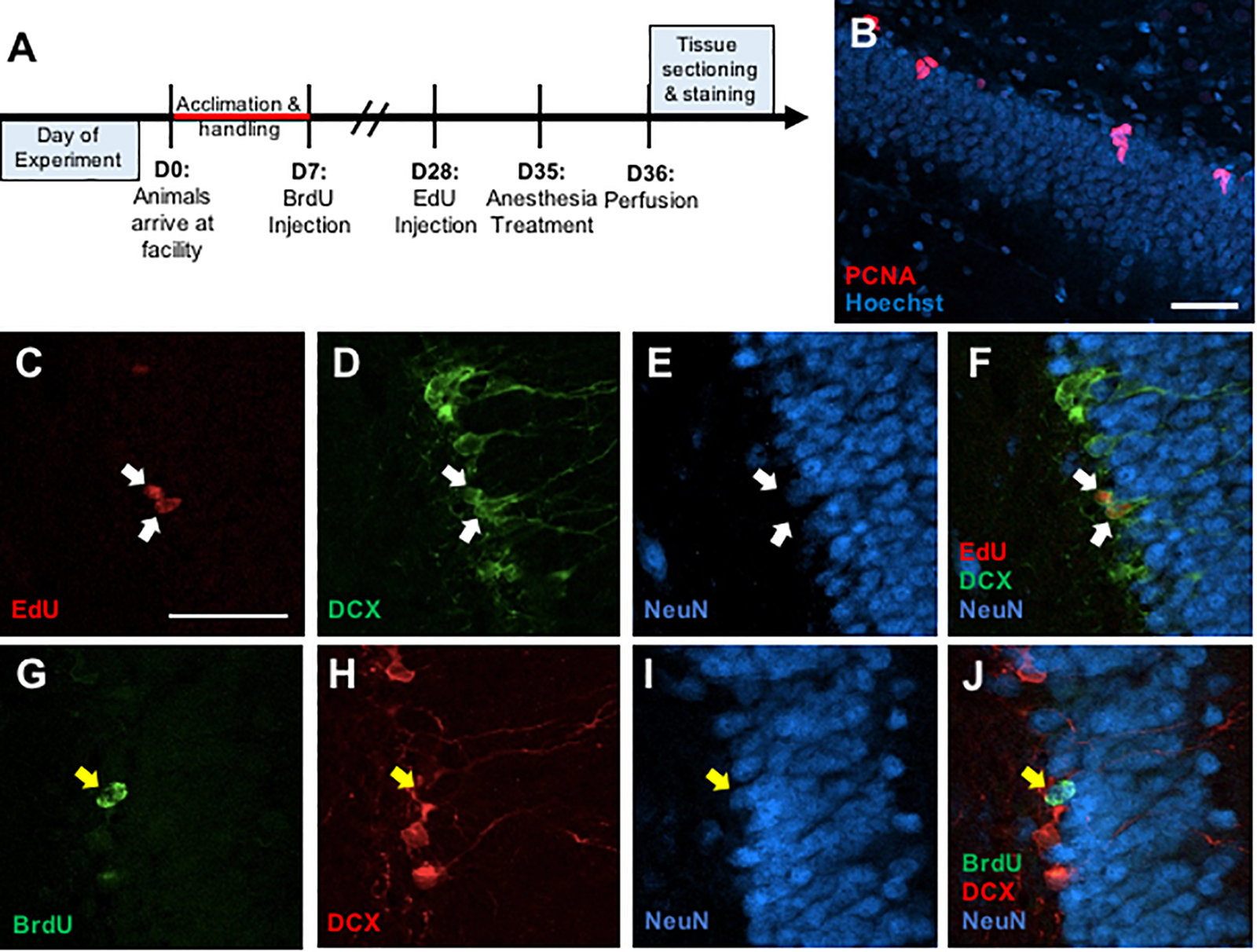

Figure 1. (A) Timeline depicting experimental design. (B) Representative photomicrograph of coronal section through the adult dentate gyrus granule cell layer showing immunostaining for PCNA (red) counterstained with Hoescht (blue). (C–F) Representative confocal images illustrating colocalization of EdU+ cells (C) with immature neuronal marker doublecortin (DCX) (D), but no co-expression with mature neuronal marker NeuN (E) and a merged image (F). (G–J) Representative confocal images showing colocalization of BrdU+ cells (G) with NeuN (H), but no colocalization with DCX (I), and a merged image (J). Scale bar = 50 μm.

One week after EdU treatment (1 month after BrdU treatment, P84), animals were randomly assigned to one of the following sedative treatment groups: control, isoflurane, propofol, midazolam, or dexmedetomidine. Control animals received an i.p. injection of 0.9% saline and were immediately returned to their home cages. All other animals were sedated for 4 h. Body temperature was regulated using a heating pad, and breathing patterns were monitored for respiratory distress. Isoflurane was administered with a vaporizer using 4% isoflurane to induce sedation and 1.5–2% isoflurane for maintenance delivered in 2 L/min O2 via nose cone. Propofol (90 mg/kg/dose), midazolam (8.0 mg/kg/dose), and dexmedetomidine (0.1 mg/kg/dose) were administered via i.p. injections over a 4-h period with a full dose administered to maintain sedation approximately every hour, or earlier if the rat made any movements suggesting recovery from sedation. After 4 h of sedation, all animals remained on heating pads until they regained consciousness (∼5–20 min) and then placed back into their home cages.

Tissue Collection and Processing

All animals were perfused the day after anesthesia exposure (P85). Rats were given an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and then transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in cold 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Brains were postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and then transferred to 20% sucrose solution and stored at 4°C until the brains sank. All brains were coronally sectioned at 40 μm on a sliding microtome into 1:12 series containing the entire DG (bilateral). Sections were stored at 4°C in PBS with 0.1% sodium azide until they were stained.

Single-Label PCNA Immunofluorescent Staining

Free-floating sections were rinsed in PBS for 15 min then in 0.1% sodium borohydride for 10 min at room temperature to reduce autofluorescence. After a 30-min PBS rinse, the sections were placed in 0.1 M citric acid (pH = 6.0) for 15 min at 90°C. Sections were rinsed in PBS for 30 min, blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 3% donkey serum for 30 min, and incubated in monoclonal mouse anti-PCNA antibody (1:20,000, sc-56; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID: AB_628110) for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were then rinsed in PBS for 30 min and incubated in a secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-mouse, 1:250, A-31570, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_2536180) for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were washed in PBS for 30 min and then incubated in Hoechst 33258 counterstain (1:1000, Sigma) for 10 min. All sections were washed in PBS for 30 min, mounted onto gelatin-subbed slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped under PVA-DABCO mounting media (Figure 1B).

EdU/DCX/NeuN Immunofluorescent Staining

Free-floating sections were rinsed in PBS for 30 min. Then, sections were rinsed in PBS for 30 min and then blocked in PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X-100 and 3% donkey serum for 30 min. Incubation in monoclonal goat anti-DCX (1:200, sc-8066, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and monoclonal mouse anti-NeuN (1:250, MAB377, Chemicon) occurred for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were then rinsed in PBS for 30 min and incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat (1:250, A-11055, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-mouse (1:250, A-31571, Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. After a 15-min rinse in PBS, sections were rinsed in a 3% BSA solution for 20 min at RT. Then, sections were incubated in 0.5% Triton-X-100 solution. Following a 10-min rinse in PBS, sections were placed in Click-iT EdU reaction cocktail (C10638, Invitrogen) for 30 min. The sections were given a final rinse in PBS for 20 min and then mounted onto gelatin-subbed slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped under PVA-DABCO mounting media (Figures 1C–F).

BrdU/DCX/NeuN Immunofluorescent Staining

Free-floating sections were rinsed in PBS for 30 min. Then, the sections were incubated in 2N HCl for 60 min at 37°C. Afterward, the sections were rinsed in PBS for 30 min and then blocked in PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X-100 and 3% donkey serum for 30 min. The sections placed in monoclonal rat anti-BrdU (1:1000, OBT0030; Accurate, RRID: AB_2313756), monoclonal goat anti-DCX (1:200, sc-8066, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID: AB_2088494), and monoclonal mouse anti-NeuN (1:250, MAB377, Chemicon, RRID: AB_2298772) at 4°C for 48 h. Sections were then rinsed in PBS for 30 min and incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rat (1:250, A-21208, Invitrogen, RRID: 2535794), Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-goat (1:250, A-21432, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_2535853), and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-mouse (1:250, A-31571, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_162542) for 2 h at room temperature. Following a 30-min rinse in PBS, all sections were mounted onto gelatin-subbed slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped under PVA-DABCO mounting media (Figures 1G–J).

Data Collection

For all analyses, slides were coded to blind the investigator to treatment groups. The single-label counts (i.e., PCNA, BrdU, and EdU) were conducted using an Olympus BX51 microscope under epi-illumination using an UPlanS Apo 40× (0.9 NA) objective. The rostral-caudal extent of the DG was analyzed (10–12 bilateral sections) for each animal. PCNA-positive (+) and EdU+ cells were visualized using a TRITC epifluorescence filter and identified by the presence of a bright orange nuclear stain. BrdU+ cells were visualized by a FITC epifluorescence filter and identified by the bright green nuclear staining. DG area and volume were not controlled for as the single-labeled brain tissue was used to assess total number of PCNA+, EdU+, or BrdU+ cells. The total number of single-labeled cells was determined by summing the number of positively stained cells across all sections analyzed. Immunolabeled sections were analyzed using a Nikon C2+ confocal laser-scanning microscope with a Plan Apochromat 20X (0.75 NA) objective. All confocal images were captured with 488, 561, and 647 nm laser exposures. 50 BrdU+ and 50 EdU+ cells in the DG of each animal were analyzed using a z-stack orthogonal viewer to verify colocalization of BrdU and EdU with DCX or NeuN. The first 25 cells identified from dorsal sections and first 25 cells from ventral sections were chosen. Z-stacks were created at a 0.85 μm intervals throughout the 40 μm section to confirm double-labeling of BrdU-ir cells.

Statistical Analysis

To examine group differences in total numbers of cells labeled with PCNA, BrdU, and EdU, a two-way ANOVA was run using treatment group (anesthetic or control) and sex as factors. For the immunofluorescence analyses, a two-way ANOVA (treatment group by sex) was used to determine whether the% colocalization of BrdU/DCX, BrdU/NeuN, EdU/DCX, and EdU/NeuN differed between treatment groups. For all analyses, a significance value of p < 0.05 was used and significant results were followed by a Tukey's post hoc test.

Results

Midazolam and Dexmedetomidine Reduce Cell Proliferation in the DG of Adult Rats

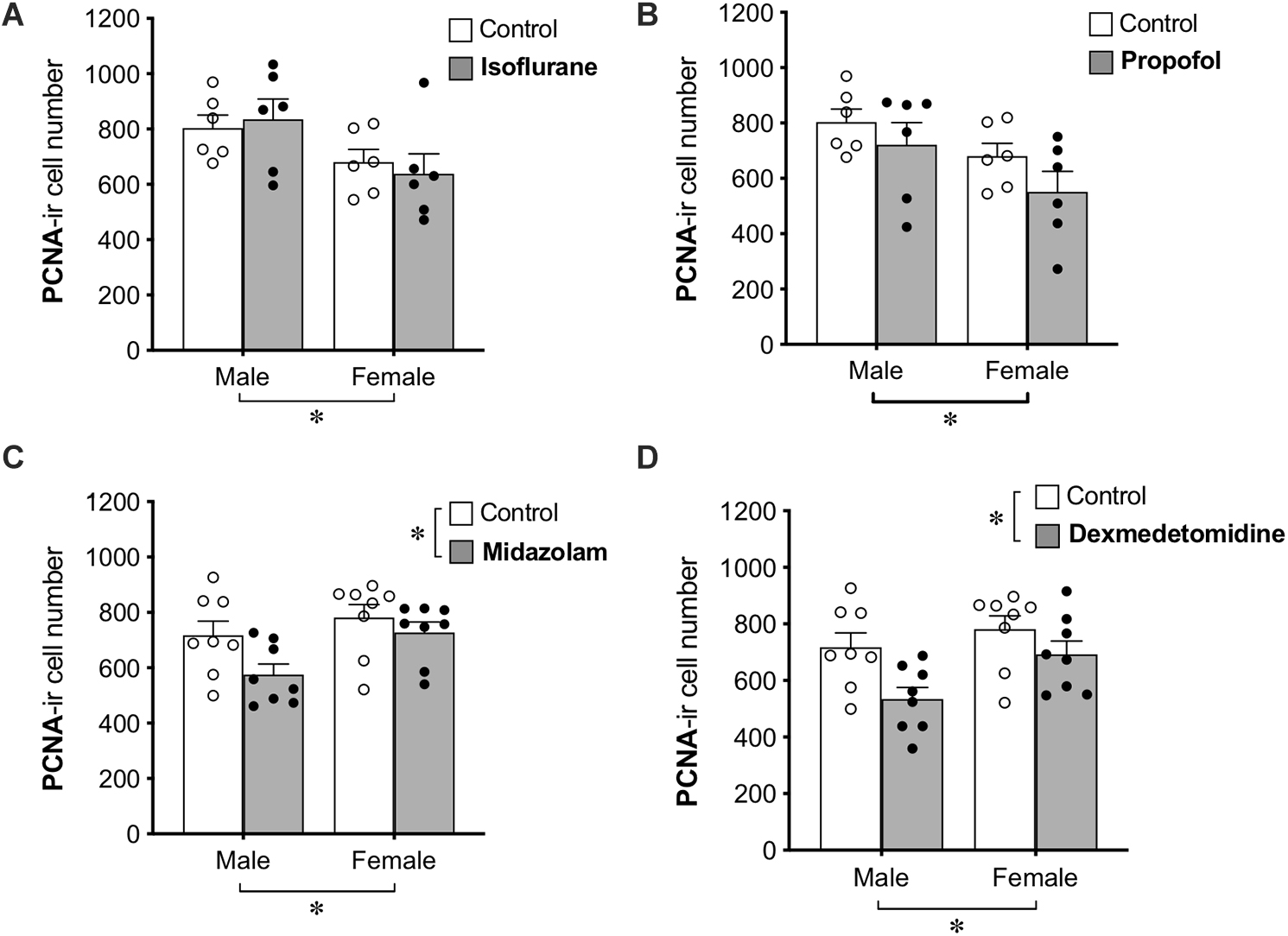

Group differences in cell proliferation were assessed by counting the total number of PCNA+ cells in the DG (Figure 2). No main effect of treatment was found for propofol treatment, but a main effect of sex difference was detected, with female rats showing ∼20% fewer PCNA+ cells compared to males. Similarly, no main effect of isoflurane treatment was observed, but female rats had significantly lower PCNA+ cell counts than males.

Figure 2. Administration of midazolam and dexmedetomidine reduces cell proliferation in dentate gyrus of adult rats. Neither isoflurane (A) nor propofol (B) significantly affected the number of PCNA+ cells in the DG of either sex. Both midazolam (C) and dexmedetomidine (D) significantly reduced cell proliferation in the DG. There were no significant sex × treatment interactions for any drug, but main effects of sex in different directions and a lack of sex effect in control animals suggest possible undetected interactions. ∗ p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Treatment with midazolam significantly decreased PCNA+ cell number by 13%, and treatment with dexmedetomidine significantly decreased PCNA+ cell number by 17%. Both of these analyses also showed main effects of sex with male rats having fewer PCNA+ cells than females. Neither analysis demonstrated a significant interaction between sex and treatment, but no sex difference was observed in control animals (Table 1), suggesting that the sex difference may have been driven by greater reduction of cell proliferation by sedation in males compared to females.

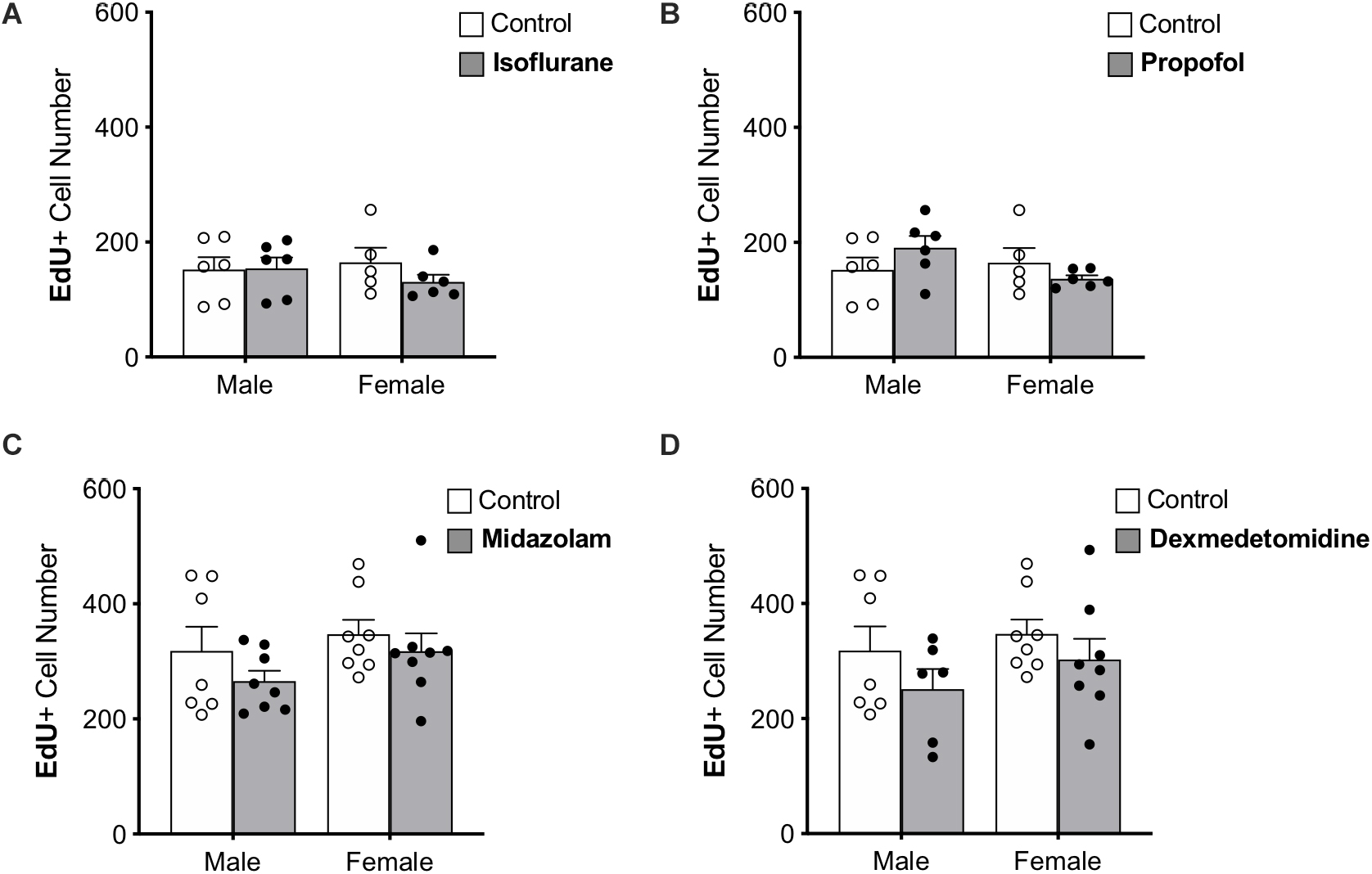

Figure 3. Treatment with anesthesia does not change the number of 7-day-old neurons in the dentate gyrus of adult male and female rats. No significant main effects of treatment or sex was observed when rats were administered (A) isoflurane, (B) propofol, (C) midazolam, or (D) dexmedetomidine. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

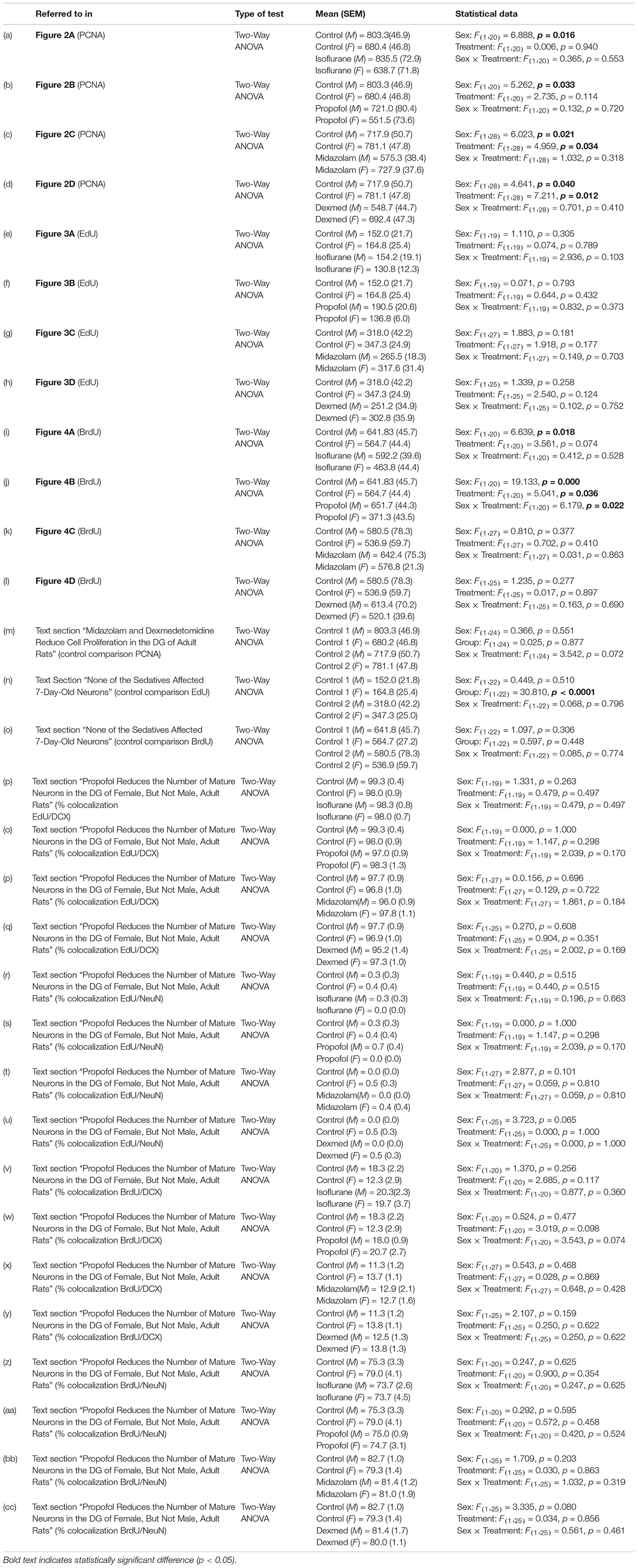

Table 1. Statistical analyses.

None of the Sedatives Affected 7-Day-Old Neurons

Immature neurons were quantified by counting the total number of DG cells labeled with EdU administered 7 days prior to sedation (Figure 3). Approximately twice as many EdU+ cells were counted in the first set of control rats (used for propofol and isoflurane experiments) than in the second (used for midazolam and dexmedetomidine experiments); this difference that may be related to the different sources of EdU used for the two groups. However, as each drug-treated group was compared with animals injected at the same time with the same EdU solution, the differences seen in controls should not affect comparisons. No other differences were found between control groups (Table 1).

None of the sedatives affected the number of EdU+ cells in the DG. In addition, no sex differences were observed in any analysis (Table 1).

The proportions of EdU+ cells that expressed DCX, an immature neuron marker, and NeuN, a mature neuronal marker were assessed. More than 95% of EdU+ cells colocalized with DCX and less than 1% co-expressed NeuN in each group, suggesting that nearly all 7-day old cells in the DG were immature neurons as expected. No significant differences were observed in the proportions of EdU+ cells co-expressing either marker, providing no indication that the rate of maturation is affected by sex or sedatives.

Propofol Reduces the Number of Mature Neurons in the DG of Female, but Not Male, Adult Rats

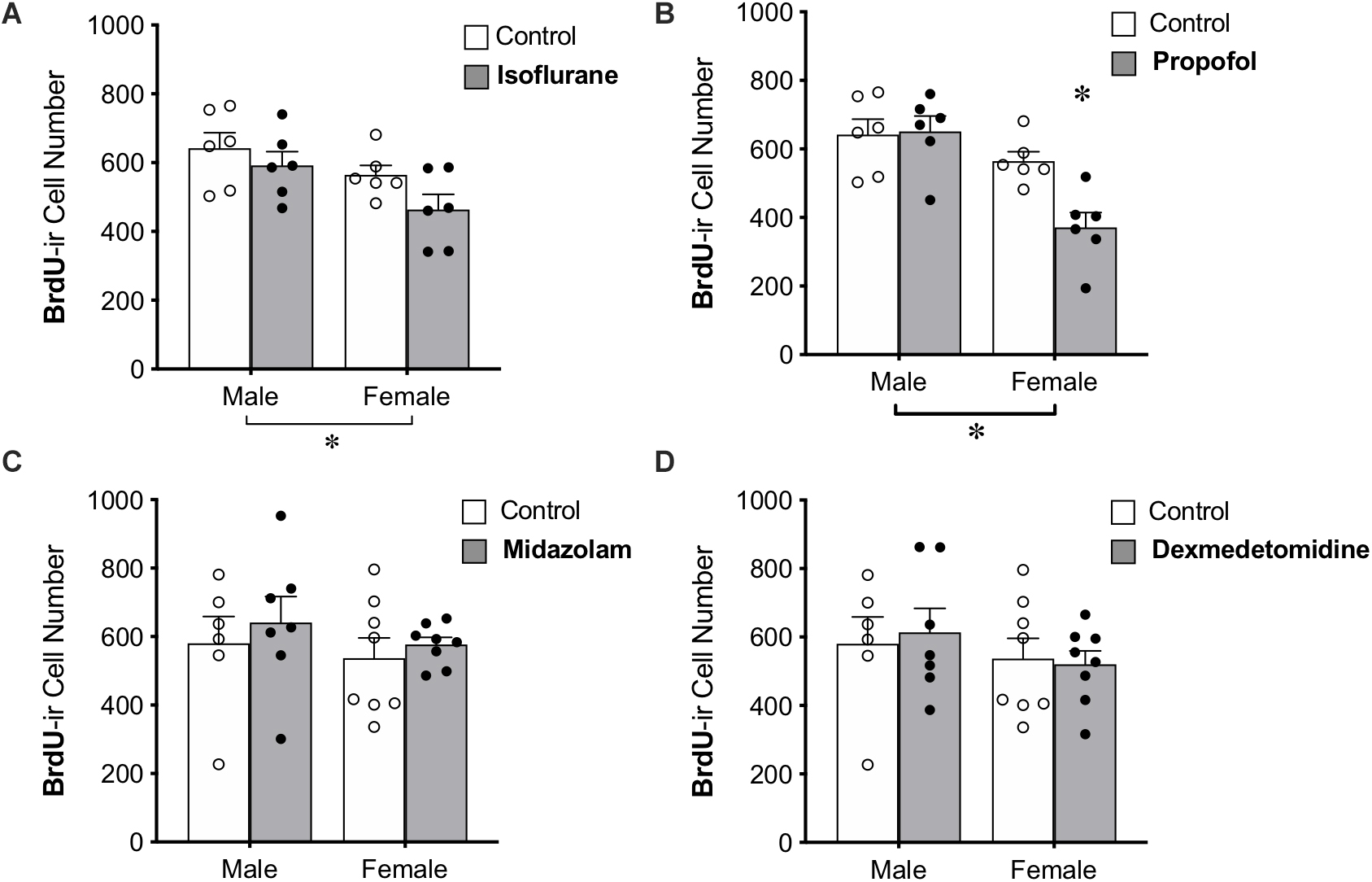

BrdU was administered to all animals 28 days prior to anesthesia exposure to label adult-born neurons that are likely to be mature enough to be integrated into functional neural circuits and able to affect behavior (Snyder et al., 2009b; Gonçalves et al., 2016; Weeden et al., 2019), though new neurons continue to mature morphologically for several more weeks (John et al., 2020). Treatment with propofol showed a sex by treatment interaction, in which propofol decreased BrdU+ cell counts in female rats (by 34%) but not in male rats (Table 1 and Figure 4B). This group also showed significant main effects of sex and treatment (Table 1).

Figure 4. Administration of propofol reduced the number of 4-week-old neurons in the dentate gyrus in adult female, but not male, rats. (A) No significant main effect of treatment was observed when rats were administered isoflurane. (B) Female rats given propofol has significantly fewer BrdU+ cells in the DG than males treated with propofol and both male and female controls. Overall, female rats had significantly fewer BrdU+ cells than males, regardless of treatment with propofol or isoflurane. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test between all groups ∗ p < 0.05. There was no significant main effect of sex or treatment or interaction when male and female rats were given (C) midazolam or (D) dexmedetomidine. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Administration of isoflurane did not significantly affect the number of BrdU+ cells, but a sex difference was identified with females having 17% fewer BrdU+ cells in the DG than males (Table 1 and Figure 4A). No main effects of treatment or sex were detected for midazolam or dexmedetomidine (Figures 4C,D).

Immunofluorescent labeling was used to examine the proportion of BrdU+ cells co-expressing DCX or NeuN in the DG. On average, 11–21% of BrdU+ cells colocalized with DCX and 74–83% of BrdU+ cells co-expressed NeuN in each group, suggesting that most of the cells had matured by this timepoint. No significant differences were found in the colocalization of BrdU+ cells with DCX or NeuN across groups, providing no evidence for effects of sex or sedation on maturation (Table 1).

Discussion

The current study examined the effects of four different sedatives on adult neurogenesis in the DG of adult male and female rats. By using two cell birthdate markers, BrdU and EdU, and an endogenous cell proliferation marker, PCNA, we were able to assess the effects of anesthesia on three distinct cell populations and found that cell age affects vulnerability to the pharmacological effects of sedatives. Specifically: (1) prolonged treatment with midazolam and dexmedetomidine, but not isoflurane or propofol, reduced cell proliferation in the DG of male and female adult rats 24 h after sedation; (2) none of the tested sedatives affected the number of immature neurons (7 days old) in the DG of either sex; and (3) prolonged sedation with propofol reduced the number of relatively mature adult-born neurons (28 days old) specifically in female rats. These results demonstrate that anesthesia can influence adult hippocampal neurogenesis in a sex-, maturation stage-, and drug-dependent manner.

Neuropharmacological Mechanisms of Sedatives

As they are currently understood, the specific pharmacological actions of the sedatives used in this study cannot readily explain their differential effects on adult neurogenesis. Though isoflurane, propofol, and midazolam act at different sites on the GABAA receptor (Olkkola and Ahonen, 2008; Vanlersberghe and Camu, 2008) they are all positive allosteric modulators (Schüttler and Schwilden, 2008). Yet only propofol detectably affected survival of maturing granule cells. This effect of propofol on neurogenesis could potentially occur via reported secondary sites of action such as cannabinoid receptors or TRP channels (Patel et al., 2003; Jin et al., 2004; Vennekens et al., 2012; Nishimoto et al., 2015; Rodrigues et al., 2017).

Our investigation of cell proliferation found that dexmedetomidine and midazolam, which act on completely different receptors, both reduced neuronal precursor proliferation. However, despite their disparate direct actions, both drugs are believed to produce their sedative effects through actions, direct or indirect, on GABAergic activity. Midazolam, a benzodiazepine, acts directly at the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor to increase channel opening. An in vitro study found that midazolam reduced proliferation of isolated neural stem cells (Zhao et al., 2012), suggesting that it may act directly on granule cell precursors to inhibit proliferation. Dexmedetomidine, in contrast, is a highly specific α2-adrenergic agonist. Its activation of adrenergic receptors is believed to produce sedative effects by inhibiting the release of norepinephrine, which then disinhibits downstream GABAergic neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (Olkkola and Ahonen, 2008), or other recently identified anesthesia-inducing cell populations (Sukhotinsky et al., 2016; Jiang-Xie et al., 2019), resulting in sedation. A similar circuit involving noradrenergic inhibition of GABAergic interneurons is present in the DG as well (Harley, 2007) and could potentially drive changes in cell proliferation. Interestingly, depletion of norepinephrine using a noradrenergic neurotoxin decreases cell proliferation in the hippocampus of adult male rats (Kulkarni et al., 2002), similar to the effects of dexmedetomidine observed in this study.

Midazolam and dexmedetomidine may decrease neuronal precursor proliferation through a common pathway involving GABAergic signaling, but this would not explain why isoflurane and propofol do not have similar anti-proliferative effects. An alternative explanation relates to secondary aspects of the sedation experience. These light sedatives leave human patients with increased awareness during sedation (McQuaid and Laine, 2008; Schüttler and Schwilden, 2008; Valentine et al., 2012; Scott-Warren and Sebastian, 2016) and slower or poorer recovery post-sedation (Kong et al., 1989; Garrity et al., 2014), particularly when used to maintain sleep (Olkkola and Ahonen, 2008). This prolonged twilight state could be stressful for the animal, leading to inhibition of precursor proliferation (Glasper et al., 2012; Koutmani and Karalis, 2015).

Effect of Sedatives on Cell Proliferation

We found no change in cell proliferation 1 day after isoflurane or propofol. This is consistent with previous studies showing no significant changes at this same time point after isoflurane (Stratmann et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010; Erasso et al., 2013) or propofol (Erasso et al., 2013). Cell proliferation was also unaffected by these sedatives when given during sedation in one study (Tung et al., 2008) but was decreased by isoflurane in another (Stratmann et al., 2009). Intriguingly, two studies found that cell proliferation is increased 4 days after isoflurane, and may remain increased for as long as 16 days (Stratmann et al., 2009, 2010), suggesting a rebound and possible net increase in neuron production after isoflurane treatment.

Few studies have examined the effects of light sedatives such as midazolam and dexmedetomidine on neurogenesis. One study found reduced cell proliferation in the DG of neonatal rats following midazolam treatment (Giri et al., 2018), consistent with what we observed here in the adult rat. Previous work on dexmedetomidine found that this sedative had no effect on cell proliferation during the sedation period (Tung et al., 2008), consistent with the time-dependent effects of isoflurane described above. Taken together, these results suggest that cell proliferation is inhibited for a period of time after recovery from sedation and that midazolam and dexmedetomidine are more likely to produce this inhibitory effect. As discussed earlier, it is possible that increased stress levels contribute to the disparate findings on cell proliferation observed between light and deep sedatives.

Differential Effects of Sedatives on Survival at Distinct Stages of Adult Neurogenesis

In addition to its effects on cell proliferation, we found that sedation can inhibit survival of adult-born neurons in the DG. In adulthood, most new cells die before functional integration into existing neural circuits (Dayer et al., 2003; Snyder et al., 2009a). Survival of the new neurons is believed to depend on their incorporation into active circuits and the resulting high rate of synaptic input and uptake of neurotrophic factors (Cao et al., 2004; Sairanen et al., 2005; Scharfman et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2008). In neonatal rats, propofol exposure disrupts the signaling pathway of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a neurotrophic factor important for neuronal survival (Zhong et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018).

We observed no effect on survival of newly-generated cells from midazolam or dexmedetomidine, the two sedatives that affect cell proliferation. This is the first study to examine the role of either of these sedatives on new neuron survival, though a previous study showed no effect of other benzodiazepines on survival of 4- to 14-day-old granule cells (Karten et al., 2006). We also found no effect of isoflurane on survival of 7- or 28-day old cells, consistent with an earlier study of isoflurane effects in male rats that showed no changes in survival of 8-day old or 21-day old neurons (Erasso et al., 2013). However, another study found granule cell death induced by isoflurane that peaked when cells were about 2 weeks old (Hofacer et al., 2013), suggesting that the effect of isoflurane may be limited to a very specific time window that was not captured in the current study. Propofol reduced the number of 28-day old, but not 7-day-old neurons in the DG of female rats in the current study. A previous study found that propofol decreased the survival of 17-day-old, but not 11-day-old, neurons in mixed male and female mice (Krzisch et al., 2013), hinting at the possibility that the window of sensitivity may be longer for propofol than for isoflurane and for cells in females than for cells in males. Together, these findings support the idea that vulnerability to anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity may depend more on the age of cells rather than the age of the subject (Vutskits and Xie, 2016) but is both sex- and drug-dependent.

Sex Differences in Adult Neurogenesis Following Sedation

In the isoflurane and propofol analyses, we observed a main effect of sex, with female rats having lower levels of cell proliferation than males in the DG. In the midazolam and dexmedetomidine analyses, we found the opposite effect of sex, with females having higher rates of cell proliferation than males, as seen in significant main effects of sex. However, analyzing the control groups alone showed no effect of sex, suggesting that the sex differences in both directions may have resulted from treatment with sedatives, despite a lack of significant sex by drug interactions. In the literature, reports on baseline sex differences in cell proliferation vary depending on specific experimental parameters. Several studies assessing cell proliferation, specifically, in the adult dentate gyrus have found no sex differences under baseline conditions in laboratory rats or mice, or wild-caught voles, chipmunks or squirrels (Barker et al., 2005; Barha et al., 2011; Spritzer et al., 2017; Tzeng et al., 2017). Previous studies have found an estrogen- and estrous cycle-dependent enhancement of new neurons in female rats and voles 1–7 days after labeling (Galea and McEwen, 1999; Tanapat et al., 1999), suggesting a sex difference in the survival time course for new neurons. However, this difference is no longer apparent after 28 days (Galea and McEwen, 1999; Tanapat et al., 1999). The lack of sex difference in baseline numbers of 7- or 28-day-old cells labeled with EdU or BrdU in the current study is consistent with this and suggests that the sex difference in early cell survival is no longer detectable after a week.

We identified a sex difference in the effects of propofol, which reduced survival of 28-day old neurons in the adult hippocampus in females but not males. It is unclear how propofol might affect males and females differently, but it could potentially be related to differences in the maturation rate of new granule neurons. Death of adult-born granule cells is normally undetectable after 28 days in male rats (Dayer et al., 2003), but a recent study in adult rats showed that maturation and attrition of new cells in the DG is prolonged in females relative to males (Yagi et al., 2019). A change in the maturation time course could shift or lengthen the window of susceptibility to a propofol-induced activity decrease in new neurons in females relative to males. Future studies will need to delineate the full window of new neuron susceptibility in females and determine whether a critical window for propofol effects on survival exists in male rats at an earlier time point.

Conclusion

The use of anesthesia is ubiquitous in both research and clinical settings. It is therefore important for future studies, especially those addressing neurogenesis, to consider sex, type of anesthetic used, and age of newly-born cells when interpreting results. Adult neurogenesis requires the coordinated timing of several independent processes, including cell proliferation, neuronal maturation, and survival. Our results indicate that different sedatives can affect different phases of neurogenesis. Inhibiting cell proliferation and increasing cell death both have the same net effect of decreasing the number of functional new neurons, possibly resulting in cognitive or emotional impairment (Cameron and Glover, 2017; Karlsson et al., 2018; Weeden et al., 2019). However, behavioral impairments resulting from these two effects would likely be observed at different time points after sedation; effects on nearly-mature neurons should have almost immediate consequences, while changes in proliferation would impact behavior only after a delay of several weeks. Changes in cell proliferation may also be less likely to produce functional impairments than effects on older neurons because the number of new neurons can be normalized during maturation via altered rates of survival (Tanapat et al., 1999, 2001; Snyder et al., 2009b). The expected duration of functional impairments due to decreases in adult neurogenesis following sedation is unclear but would depend on how long proliferation is diminished, which appear to be short-lived (Lin et al., 2013), and the age range of maturing cells susceptible to sedation-induced loss. Future studies will be needed to determine whether sedation-induced decreases in neurogenesis result in detectable cognitive and behavioral changes, both in experimental models and in human patients.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Author Contributions

JK planned the study, designed and conducted experiments, carried out data and statistical analyses, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. NB conducted experiments, carried out data collection, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. HC planned and designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the scientific interpretations.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH (ZIAMH002784 to HC).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Barha, C. K., Brummelte, S., Lieblich, S. E., and Galea, L. A. M. (2011). Chronic restraint stress in adolescence differentially influences hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in male and female rats. Hippocampus 21, 1216–1227. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20829

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barker, J. M., Wojtowicz, J. M., and Boonstra, R. (2005). Where's my dinner? Adult neurogenesis in free-living food-storing rodents. Genes Brain Behav. 4, 89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00097.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bayer, S. A., Altman, J., Russo, R. J., and Zhang, X. (1993). Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neurotoxicology 14, 83–144.

Google Scholar

Beery, A. K., and Zucker, I. (2011). Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Broad, K. D., Hassell, J., Fleiss, B., Kawano, G., Ezzati, M., Rocha-Ferreira, E., et al. (2016). Isoflurane exposure induces cell death, microglial activation and modifies the expression of genes supporting neurodevelopment and cognitive function in the male newborn piglet brain. PLoS One 11:e0166784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166784

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cabrera, O. H., Gulvezan, T., Symmes, B., Quillinan, N., and Jevtovic-Todorovic, V. (2020). Sex differences in neurodevelopmental abnormalities caused by early-life anaesthesia exposure: a narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 124, e81–e91. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.032

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Callaway, J. K., Wood, C., Jenkins, T. A., Royse, A. G., and Royse, C. F. (2016). Isoflurane in the presence or absence of surgery increases hippocampal cytokines associated with memory deficits and responses to brain injury in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 303, 44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.01.032

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cameron, H. A., and Glover, L. R. (2017). Adult neurogenesis: beyond learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015006.ADULT

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cao, L., Jiao, X., Zuzga, D. S., Liu, Y., Fong, D. M., Young, D., et al. (2004). VEGF links hippocampal activity with neurogenesis, learning and memory. Nat. Genet. 36, 827–835. doi: 10.1038/ng1395

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Culley, D. J., Baxter, M., Yukhananov, R., and Crosby, G. (2003). The memory effects of general anesthesia persist for weeks in young and aged rats. Anesth. Analg. 96, 1004–1009. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000052712.67573.12

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Culley, D. J., Baxter, M. G., Crosby, C. A., Yukhananov, R., and Crosby, G. (2004a). Impaired acquisition of spatial memory 2 weeks after isoflurane and isoflurane-nitrous oxide anesthesia in aged rats. Anesth. Analg. 99, 1393–1397. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000135408.14319.CC

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Culley, D. J., Baxter, M. G., Yukhananov, R., and Crosby, G. (2004b). Long-term impairment of acquisition of a spatial memory task following isoflurane-nitrous oxide anesthesia in rats. Anesthesiology 100, 309–314.

Google Scholar

Culley, D. J., Xie, Z., and Crosby, G. (2007). General anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity: an emerging problem for the young and old? Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 20, 408–413. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282efd18b

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dayer, A. G., Ford, A. A., Cleaver, K. M., Yassaee, M., and Cameron, H. A. (2003). Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 460, 563–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.10675

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Deng, M., Hofacer, R. D., Jiang, C., Joseph, B., Hughes, E. A., Jia, B., et al. (2014). Brain regional vulnerability to anaesthesia-induced neuroapoptosis shifts with age at exposure and extends into adulthood for some regions. Br. J. Anaesth. 113, 443–451. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet469

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Erasso, D. M., Camporesi, E. M., Mangar, D., and Saporta, S. (2013). Effects of isoflurane or propofol on postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in young and aged rats. Brain Res. 1530, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.035

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Erasso, D. M., Chaparro, R. E., Quiroga del Rio, C. E., Karlnoski, R., Camporesi, E. M., and Saporta, S. (2011). Quantitative assessment of new cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus and learning after isoflurane or propofol anesthesia in young and aged rats. Brain Res. 1441, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.025

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Galea, L. A. M., and McEwen, B. S. (1999). Sex and seasonal differences in the rate of cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of adult wild meadow voles. Neuroscience 89, 955–964.

Google Scholar

Garrity, A. G., Botta, S., Lazar, S. B., Swor, E., Vanini, G., Baghdoyan, H. A., et al. (2014). Dexmedetomidine-induced sedation does not mimic the neurobehavioral phenotypes of sleep in Sprague Dawley rat. Sleep 38, 73–84. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4328

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ge, S., Sailor, K. A., Ming, G. L., and Song, H. (2008). Synaptic integration and plasticity of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J. Physiol. 586, 3759–3765. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155655

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gertler, R., Brown, H. C., Mitchell, D. H., and Silvius, E. N. (2001). Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 14, 13–21.

Google Scholar

Giri, P. K., Lu, Y., Lei, S., Li, W., Zheng, J., Lu, H., et al. (2018). Pretreatment with minocycline improves neurogenesis and behavior performance after midazolam exposure in neonatal rats. Neuroreport 29, 153–159. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000937

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Glasper, E. R., Schoenfeld, T. J., and Gould, E. (2012). Adult neurogenesis: optimizing hippocampal function to suit the environment. Behav. Brain Res. 227, 380–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Harley, C. W. (2007). Norepinephrine and the dentate gyrus. Prog. Brain Res. 163, 299–318.

Google Scholar

Hill, A. S., Sahay, A., and Hen, R. (2015). Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to reduce anxiety and depression-like behaviors. Neurop 40, 2368–2378. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.85

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hofacer, R. D., Deng, M., Ward, C. G., Joseph, B., Hughes, E. A., Jiang, C., et al. (2013). Cell age-specific vulnerability of neurons to anesthetic toxicity. Ann. Neurol. 73, 695–704. doi: 10.1002/ana.23892

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hovaguimian, F., Tschopp, C., Beck-Schimmer, B., and Puhan, M. (2018). Intraoperative ketamine administration to prevent delirium or postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 62, 1182–1193. doi: 10.1111/aas.13168

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, J., Jing, S., Chen, X., Bao, X., Du, Z., Li, H., et al. (2016). Propofol administration during early postnatal life suppresses hippocampal neurogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 1031–1044.

Google Scholar

Jevtovic-Todorovic, V., Hartman, R. E., Izumi, Y., Benshoff, N. D., Dikranian, K., Zorumski, C. F., et al. (2003). Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J. Neurosci. 23, 876–882.

Google Scholar

Jiang-Xie, L. F., Yin, L., Zhao, S., Prevosto, V., Han, B. X., Dzirasa, K., et al. (2019). A common neuroendocrine substrate for diverse general anesthetics and sleep. Neuron 102, 1053–1065.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.033

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jin, K., Xie, L., Kim, S. H., Parmentier-Batteur, S., Sun, Y., Mao, X. O., et al. (2004). Defective adult neurogenesis in CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 204–208. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.2.204

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

John, A., Cole, D., Espinueva, D., Seib, D. R., and Cooke, M. B. (2020). Adult-born hippocampal neurons undergo extended development and are morphologically distinct from neonatally-born neurons. J. Neurosci. 40, 5740–5756.

Google Scholar

Karlsson, R. M., Wang, A. S., Sonti, A. N., and Cameron, H. A. (2018). Adult neurogenesis affects motivation to obtain weak, but not strong, reward in operant tasks. Hippocampus 28, 512–522. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22950

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Karten, Y. J. G., Jones, M. A., Jeurling, S. I., and Cameron, H. A. (2006). GABAergic signaling in young granule cells in the adult rat and mouse dentate gyrus. Hippocampus 16, 312–320. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20165

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kodama, M., Satoh, Y., Otsubo, Y., Araki, Y., Yonamine, R., Masui, K., et al. (2011). Neonatal desflurane exposure induces more robust neuroapoptosis than do isoflurane and sevoflurane and impairs working memory. Anesthesiology 115, 979–991.

Google Scholar

Kong, K. L., Willatts, S. M., and Prys-roberts, C. (1989). Isoflurane compared with midazolam for sedation in the intensive care unit. BMJ 298, 1277–1280.

Google Scholar

Koutmani, Y., and Karalis, K. P. (2015). Neural stem cells respond to stress hormones: distinguishing beneficial from detrimental stress. Front. Physiol. 6:77. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00077

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Krzisch, M., Sultan, S., Sandell, J., Demeter, K., Vutskits, L., and Toni, N. (2013). Propofol anesthesia impairs the maturation and survival of adult-born hippocampal neurons. Anesthesiology 118, 602–610.

Google Scholar

Ku, B., Alvi, R. S., May, L. D. V., Hrubos, M. W., Russell, I., Stratmann, G., et al. (2010). Isoflurane does not affect brain cell death, hippocampal neurogenesis, or long-term neurocognitive outcome in aged rats. Anesthesiology 112, 305–315. doi: 10.1097/aln.0b013e3181ca33a1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kulkarni, V. A., Jha, S., and Vaidya, V. A. (2002). Depletion of norepinephrine decreases the proliferation, but does not influence the survival and differentiation, of granule cell progenitors in the adult rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 2008–2012. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02268.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Landin, J. D., Palac, M., Carter, J. M., Dzumaga, Y., Santerre-Anderson, J. L., Fernandez, G. M., et al. (2019). General anesthetic exposure in adolescent rats causes persistent maladaptations in cognitive and affective behaviors and neuroplasticity. Neuropharmacology 150, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.022

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, N., Moon, T. S., Stratmann, G., and Sall, J. W. (2013). Biphasic change of progenitor proliferation in dentate gyrus after single dose of isoflurane in young adult rats. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 25, 306–310. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e318283c3c7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McQuaid, K. R., and Laine, L. (2008). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest. Endosc. 67, 910–923. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Monk, T., Weldon, B., Garvan, C., Dede, D., van der Aa, M. T., Heilman, K., et al. (2008). Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 108, 18–30.

Google Scholar

Moreno-Jiménez, E. P., Flor-García, M., Terreros-Roncal, J., Rábano, A., Cafini, F., Pallas-Bazarra, N., et al. (2019). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 25, 554–560. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0375-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nishimoto, R., Kashio, M., and Tominaga, M. (2015). Propofol-induced pain sensation involves multiple mechanisms in sensory neurons. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 467, 2011–2020.

Google Scholar

Olkkola, K. T., and Ahonen, J. (2008). "Midazolam and other benzodiazepines," in Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Vol. 182, eds J. Schüttler and H. Schwilden (Berlin: Springer), 335–360.

Google Scholar

Palanisamy, A., Crosby, G., and Culley, D. J. (2017). EARLY gestational exposure to isoflurane causes persistent cell loss in the dentate gyrus of adult male rats. Behav. Brain Funct. 13, 10–14.

Google Scholar

Pandharipande, P., Shintani, A., Peterson, J., Truman, B. P., Wilkinson, G. R., Dittus, R. S., et al. (2006). Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology 104, 21–26.

Google Scholar

Patel, S., Wohlfeil, E. R., Rademacher, D. J., Carrier, E. J., Perry, L. T. J., Kundu, A., et al. (2003). The general anesthetic propofol increases brain N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) content and inhibits fatty acid amide hydrolase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705334

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rodrigues, R. S., Ribeiro, F. F., Ferreira, F., Vaz, S. H., Sebastião, A. M., and Xapelli, S. (2017). Interaction between cannabinoid type 1 and type 2 receptors in the modulation of subventricular zone and dentate gyrus neurogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 8:516. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00516

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sairanen, M., Lucas, G., Ernfors, P., Castrén, M., and Castrén, E. (2005). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant drugs have different but coordinated effects on neuronal turnover, proliferation, and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 25, 1089–1094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3741-04.2005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Scharfman, H., Goodman, J., Macleod, A., Phani, S., Antonelli, C., and Croll, S. (2005). Increased neurogenesis and the ectopic granule cells after intrahippocampal BDNF infusion in adult rats. Exp. Neurol. 192, 348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schüttler, J., and Schwilden, H. (2008). Modern Anesthetics: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Google Scholar

Scott-Warren, V. L., and Sebastian, J. (2016). Dexmedetomidine: its use in intensive care medicine and anaesthesia. BJA Educ. 16, 242–246. doi: 10.1093/bjaed/mkv047

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, X., Liu, Y., Xu, S., Zhao, Q., Guo, X., Shen, R., et al. (2013). Early life exposure to sevoflurane impairs adulthood spatial memory in the rat. Neurotoxicology 39, 45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.08.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Snyder, J. S., Choe, J. S., Clifford, M. A., Jeurling, S. I., Hurley, P., Brown, A., et al. (2009a). Adult-born hippocampal neurons are more numerous, faster maturing, and more involved in behavior in rats than in mice. J. Neurosci. 29, 14484–14495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1768-09.2009

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Snyder, J. S., Glover, L. R., Sanzone, K. M., Kamhi, J. F., and Cameron, H. A. (2009b). The effects of exercise and stress on the survival and maturation of adult-generated granule cells. Hippocampus 19, 898–906. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20552

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Soldin, P. O., and Mattison, R. D. (2009). Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 143–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121453

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Soumier, A., Carter, R. M., Schoenfeld, T. J., and Cameron, H. A. (2016). New hippocampal neurons mature rapidly in response to ketamine but are not required for its acute antidepressant effects on neophagia in rats. eNeuro 3:ENEURO.0116-15.2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0116-15.2016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Spritzer, M. D., Panning, A. W., Engelman, S. M., Prince, W. T., Casler, A. E., Georgakas, J. E., et al. (2017). Seasonal and sex differences in cell proliferation, neurogenesis, and cell death within the dentate gyrus of adult wild-caught meadow voles. Neuroscience 360, 155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.046

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stratmann, G., Sall, J. W., May, L. D. V., Bell, J. S., Magnusson, K. R., Rau, V., et al. (2009). Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. Anesthesiology 110, 834–848. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stratmann, G., Sall, J. W., May, L. D. V., Loepke, A. W., and Lee, M. T. (2010). Beyond anesthetic properties: the effects of isoflurane on brain cell death, neurogenesis, and long-term neurocognitive function. Anesth. Analg. 110, 431–437. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181af8015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sukhotinsky, I., Minert, A., Soja, P., and Devor, M. (2016). Mesopontine switch for the induction of general anesthesia by dedicated neural pathways. Anesth. Analg. 123, 1274–1285. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001489

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tanapat, P., Hastings, N. B., Reeves, A. J., and Gould, E. (1999). Estrogen stimulates a transient increase in the number of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat. J. Neurosci. 19, 5792–5801. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.19-14-05792.1999

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tanapat, P., Hastings, N. B., Rydel, T. A., Galea, L. A. M., and Gould, E. (2001). Exposure to fox odor inhibits cell proliferation in the hippocampus of adult rats via an adrenal hormone-dependent mechanism. J. Comp. Neurol. 437, 496–504. doi: 10.1002/cne.1297

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tung, A., Herrera, S., Fornal, C. A., and Jacobs, B. L. (2008). The effect of prolonged anesthesia with isoflurane, propofol, dexmedetomidine, or ketamine on neural cell proliferation in the adult rat. Anesth. Analg. 106, 1772–1777. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816f2004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tzeng, W. Y., Wu, H. H., Wang, C. Y., Chen, J. C., Yu, L., and Cherng, C. G. (2017). Sex differences in stress and group housing effects on the number of newly proliferated cells and neuroblasts in middle-aged dentate gyrus. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10:249. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00249

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Valentine, H., Williams, W. O., and Maurer, K. J. (2012). Sedation or inhalant anesthesia before euthanasia with CO2 does not reduce behavioral or physiologic signs of pain and stress in mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 51, 50–57.

Google Scholar

Vanlersberghe, C., and Camu, F. (2008). "Propofol," in Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, eds J. Schüttler and H. Schwilden (Berlin: Springer), 227–252.

Google Scholar

Vennekens, R., Menigoz, A., and Nilius, B. (2012). TRPs in the brain. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 163, 27–65.

Google Scholar

Weeden, C. S. S., Mercurio, J. C., and Cameron, H. A. (2019). A role for hippocampal adult neurogenesis in shifting attention toward novel stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 376:112152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112152

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yagi, S., Splinter, J. E. J., Tai, D., Wong, S., and Galea, L. A. M. (2019). Sex differences in maturation and attrition rate of adult born neurons in the hippocampus of rats. bioRxiv [Preprint] doi: 10.1101/726398

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, H., Dong, Y., Shi, H. N., Culley, D. J., et al. (2012). Anesthetics isoflurane and desflurane differently affect mitochondrial function, learning, and memory. Ann. Neurol. 71, 687–698. doi: 10.1002/ana.23536

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhao, S., Zhu, Y., Xue, R., Li, Y., Lu, H., and Mi, W. (2012). Effect of midazolam on the proliferation of neural stem cells isolated from rat hippocampus. Neural Regen. Res. 7, 1475–1482. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.19.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhong, Y., Chen, J., Li, L., Qin, Y., Wei, Y., Pan, S., et al. (2018). PKA-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway mediates propofol-induced long-term learning and memory impairment in hippocampus of rats. Brain Res. 1691, 64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.04.022

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, J., Wang, F., Zhang, J., Li, J., Ma, L., Dong, T., et al. (2018). The interplay of BDNF-TrkB with NMDA receptor in propofol-induced cognition dysfunction: mechanism for the effects of propofol on cognitive function. BMC Anesthesiol. 18:35. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0491-y

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhu, C., Gao, J., Karlsson, N., Li, Q., Zhang, Y., Huang, Z., et al. (2010). Isoflurane anesthesia induced persistent, progressive memory impairment, caused a loss of neural stem cells, and reduced neurogenesis in young, but not adult, rodents. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 1017–1030. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.274

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

macdonaldhougmenseed.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.588356/full

Post a Comment for "Can Continued Exposure to Anesthesia Cause Problems With the Brain Adults"